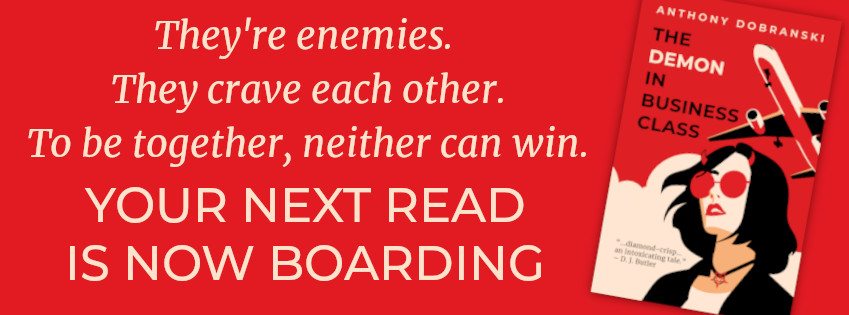

In this season of love, I’m posting Valentines to inspirations for my own novel, The Demon in Business Class. This is the fourth – find the others here.

My previous love notes were to works or creators that I followed for years. Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita happened to come into my life at the right time — I found it on a bookstore table, and bought it on a whim.

Though I use books to find styles and moods, I tend to avoid books with similar stories to ones I am currently writing, and deals with demons and thwarted love come awfully close. So I say whim, but I think inspiration. Without this great novel and its many lessons, The Demon in Business Class would be a different and worse book, if finished book at all.

The Master and Margarita is a hallucinatory horror satire, a story about capricious, florid evil challenging methodical, dull evil. The Devil wants to host a great party in Soviet Moscow, but while he can bully past greedy functionaries — or behead them, or teleport them to Yalta — he needs a willing human hostess. The desperate Margarita searches for her writer lover, crushed by the official rejection of his beautiful novel about the last days of Jesus’s earthly life. A deal is struck, one that leads through horror toward unearthly peace.

The Russian people now treasure the novel, both as a story and as one of the few surviving honest descriptions of life under Stalin. Despite demons, talking cats, magic flights over Moscow, and a grand ball by turns miraculous and ghastly, the novel also captures the injustice of ordinary life in that fear-soaked time.

In many ways, my novel opposes Bulgakov’s. My demon is an evanescence, not the intelligence in charge. Margarita embraces the demonic to restore her lover; my characters escape the fantastic for each other. Bulgakov ends with hope and love. My characters — well, read for yourself.

It’s instead that honesty and ordinariness that inspired me — really that solved my worst problem — and took The Demon in Business Class to greater breadth and depth.

My earliest concepts of Demon focused on the love story, the characters’ unsuitability for it, and what they had to go through to keep it. To highlight the opposition, I imagined a world with modern technology but also overt and obvious magic. I knew the fantastic had to be there, but I couldn’t say why, and that ignorance was in my way. I wrote 400 pages of novel and felt painted into a corner.

Bulgakov showed me my initial error. I had chosen to flavor my book in my time and with my brilliant experience, which showed me a world where fast transportation and instant communication had brought ancient cultures right up against each other, without time and understanding to moderate. I saw nations in flux, saw fusion and friction, all the while working alongside smart, ambitious people.

Having been offered all that, I was making it an aside, in favor of my own engineered fantasies, for stakes that needed over-explaining in a bubble. Many books are their own place, with no referent to our world, but I was trying to make my own small place out of a big place.

Fantasy need not be a rejection of the world as it is, because most fantasies, and horrors, form inside us, our own processing of our hopes and fears through the lens of our culture. I had a rich world to work with — the only real world, pace ecstatics and Philip K Dick. All I had to do was… be in it, in both its facts and its dreams.

So I followed Bulgakov’s example. My narrator went to the background, my plot got trimmed. My characters grew sharper, less erudite, feeling not talking. The magic became secret, costly, and hard-won — and usually inconvenient. It made for a better novel, if a more exacting one to write.

It also made for a novel that knew what it wanted to say, about where the world was going and how we might accept, reject, or stand back from it. Already the real few years since Demon‘s setting have shown it got things right.

Despite demons, star-crossed lovers, hidden conspiracies, immortals, and a single night of miracles and horror, maybe The Demon in Business Class will also read, over time, like an honest description of this period in human life.

I wonder if readers will feel as lucky not to live in my time as I do not to live in Margarita’s.