In this season of love, I’m posting Valentines to artistic inspirations for my own novel, The Demon in Business Class. This is the third – find the others here.

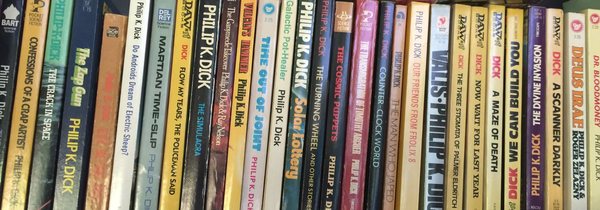

I spent my teenage years in search of Philip K. Dick. I hunted down every yellowing paperback of his I could find, in used bookstores across the United States and in other countries too. I bought and read Dick novels in the Latin Quarter, on the Spanish Steps, and in many low-end shopping malls. He was my lodestar for a decade, in the decade before his critical renaissance.

What most fascinates me in Dick’s work isn’t exactly what drives most discussions of his work: the sense of unreality he is justly famous for exploring, his Gnostic sense that the world we see is a veil over a deeper truth, be it better or worse.

I liked that, of course, because it was true. It was obvious. What I craved from him was not that knowledge, but what to do with it. I sought examples of humanity in the face of that. I wanted to explore the terror of cosmic befuddlement, to see how to survive it, and how sometimes one didn’t.

This is why my inspiration and my love goes to A Scanner Darkly, the rawest, cruelest, bleakest, least heroic of all his novels — the only one that ever made me cry, and still does.

Despite it being the only Dick novel faithfully made into a movie, it seems the least beloved. Science-fiction fans like his earlier work, where there are spaceships and androids, virtual realities and powerful psychopaths. Mystics like his later work, of religious ecstasy and passionate conviction. A Scanner Darkly is the grim, tedious nadir between them, with a main character who is neither The Matrix‘s Neo nor St. Paul: Bob Arctor, a deep-cover narcotics policeman between losers and literally faceless (thanks to special suits) desk-duty bosses, while his addiction to the drug he’s supposed to trace slowly destroys him.

The Demon in Business Class shares much with A Scanner Darkly‘s story. There are answers to hidden questions, and characters discover they’ve been serving goals they would have refused, whatever their worth to the greater good. And of course there’s a demon, more literal but as effective as addiction at dragging them down while promising not to.

Zarabeth and Gabriel are too adept at conventional reality to bottom out in the way Bob Arctor does. If Dick had written my novel, Bill Thorn would have been his Arctor, failing tragically to measure up to a goal he chose out of fear.

Demon however is a love story, something Dick never wrote (save one for a shoe). Dick never allowed his characters a companion in their grief. Zarabeth and Gabriel have each other, and the willingness to recognize the value in their bond by letting it change them.

The closest I could get to Dick’s despair was to give Zarabeth and Gabriel the understanding that their love meant giving up something their love could never fully replace. At least it’s a choice.

Without spoilers, my lovers have challenges ahead. Maybe this was another nod to Dick’s reality — the thing, as the saying goes, that doesn’t go away when you stop believing in it.

I said earlier that Zarabeth and Gabriel don’t bottom out the way Bob Arctor does. Maybe better to say, haven’t yet. There’s still time.

*Maybe I should say, the least beloved of his major works. Dick wrote nearly fifty novels, but fewer than a dozen get Library of America editions. A Scanner Darkly is, I think, the least loved of those.