In his new Slate essay, Lee Konstantinou opines that Something is Broken in Our Science Fiction.

He isn’t really talking about science-fiction, so much as its subgenre of cyberpunk, which certainly still influences science-fiction subgenre naming, from steampunk to hopepunk. I’m not sure that cyberpunk has more influence than that these days – but let’s talk cyberpunk, for now.

Konstantinou calls cyberpunk a genre where the “hacker hero (or his magic-wielding counterpart) faces a huge system of power, overcomes long odds, and finally makes the world marginally better—but not so much better that the author can’t write a sequel.”

Never mind that this is the story of many novels in many genres. It’s a poor fit to cyberpunk, which usually sweeps its anti-heroes into situations where they are fitfully, perhaps only for a moment, masters of their fate. Usually, cyberpunk contents itself with not letting things get even worse. Its antecedent is the bitter Sisyphean resignation of Philip K. Dick. It’s telling that the book Konstantinou calls a parody of cyberpunk, Snow Crash, is one of the few that really embrace his straw-man of story concept in a funny and self-aware way — though, without a sequel.

According to Wikipedia, I am twelve years older than Konstantinou. I am fifty-three, so doing the math will show those were a significant twelve years. When he was a kid, he had the hammering-down of the Berlin Wall. When I was a kid, nuclear war, waged across that wall’s spiked concrete, was such a certainty that the network ABC made a prime-time movie about it.

In that light, cyberpunk was hopeful. Ecodeath and corporate control notwithstanding, we still had a world, and satellite casinos too. To state baldly, as Konstantinou does, that “cyberpunk is arguably a kind of fiction unable to imagine a future very different from its present” ignores that the present got more hopeful after the fiction. In its day it was a vast imagining, counter to both the militarized and the utopian strains of science-fiction, and more realistically human than either.

Konstantinou also dismisses style, which is a big part of cyberpunk. It’s like faulting Edgar Allan Poe for brooding. Even in our days of smartwatches, the scene in Neuromancer where the AI Wintermute chases after Case by ringing pay-phone after pay-phone is still powerful — BBC’s recent Sherlock steals it to introduce Watson to Mycroft Holmes.

Konstantinou’s biggest error, of course, is to conflate cyberpunk with the whole of science-fiction. In this century, most good and well-regarded science-fiction books are not cyberpunk, in either setting or style. Now that so much reality has come to resemble cyberpunk, in its technofetishism and anarchic capitalism, we do need new imaginings.

Thing is, we’re getting them. There’s lots of good sci-fi, and most of it owes its predecessors. No one would call N K Jemisin cyberpunk, nor Ann Leckie, nor Cixin Liu. All of them work in older traditions, and also do many things new.

So what does Konstantinou want? For his Twitter feed to be less full of optimism and fads, it seems.

Maybe the problem is less in science-fiction than on Twitter?

Tag: futurism

-

Science-fiction is neither cyberpunk nor broken

-

Destroying Budapest

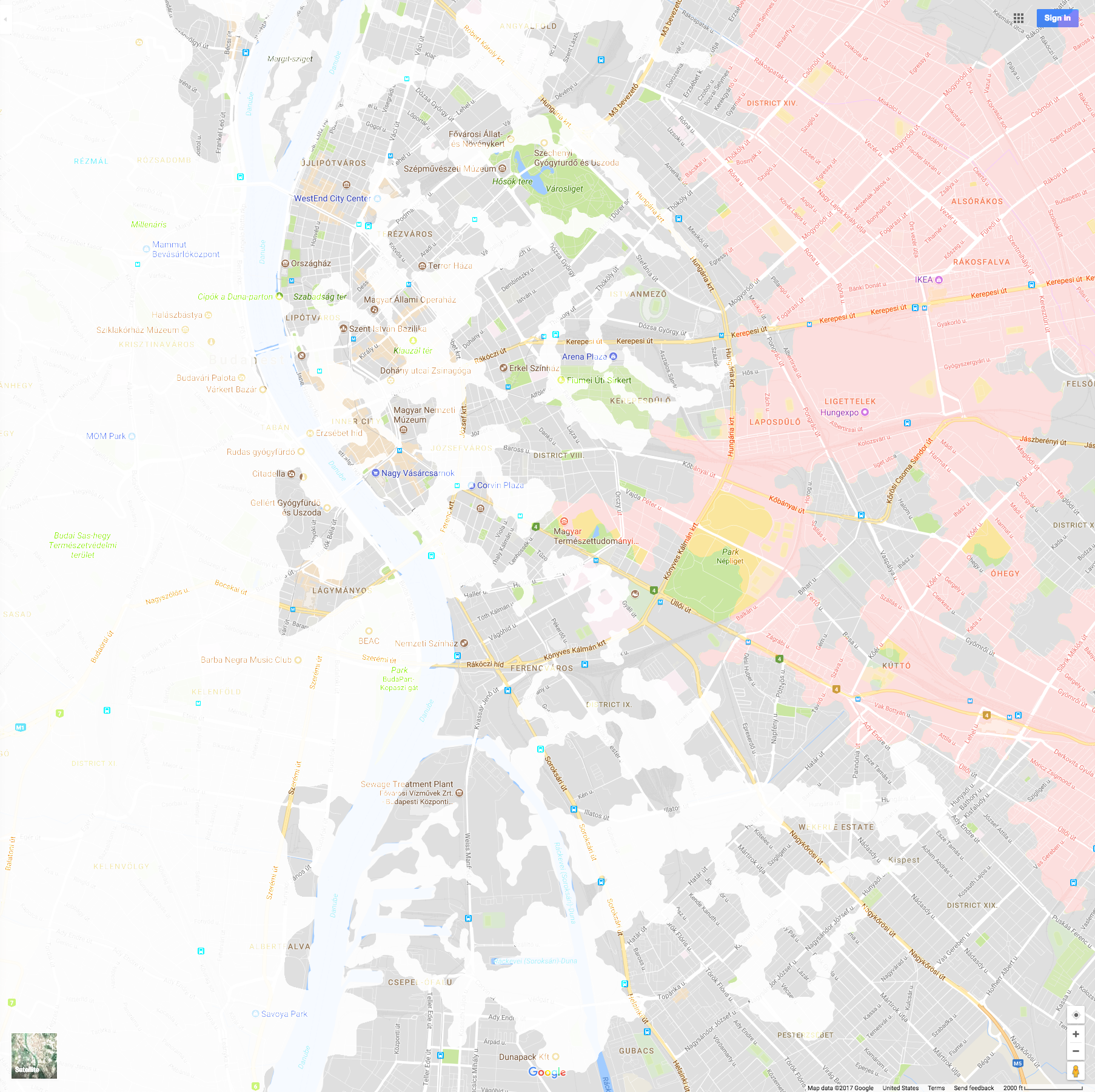

My science-fiction work-in-progress is set in a single city, and I needed to see it to imagine living in it. Welcome to Pest! Only walk on gray parts….

Budapest was a proxy in the One-Day War between Greater Russia and Umoja East Africa. Buda is now the White Lake, a boiling toxic waste of microscopic robots that eat carbon dioxide, and anything else, to make diamonds that wash on its shores. Both embargoed no-person’s-land and boomtown, Pest houses thieves, smugglers, engineers, and skaters, daredevil gladiators who jump and spin over the Lake in maglev boots, just one fall from death.

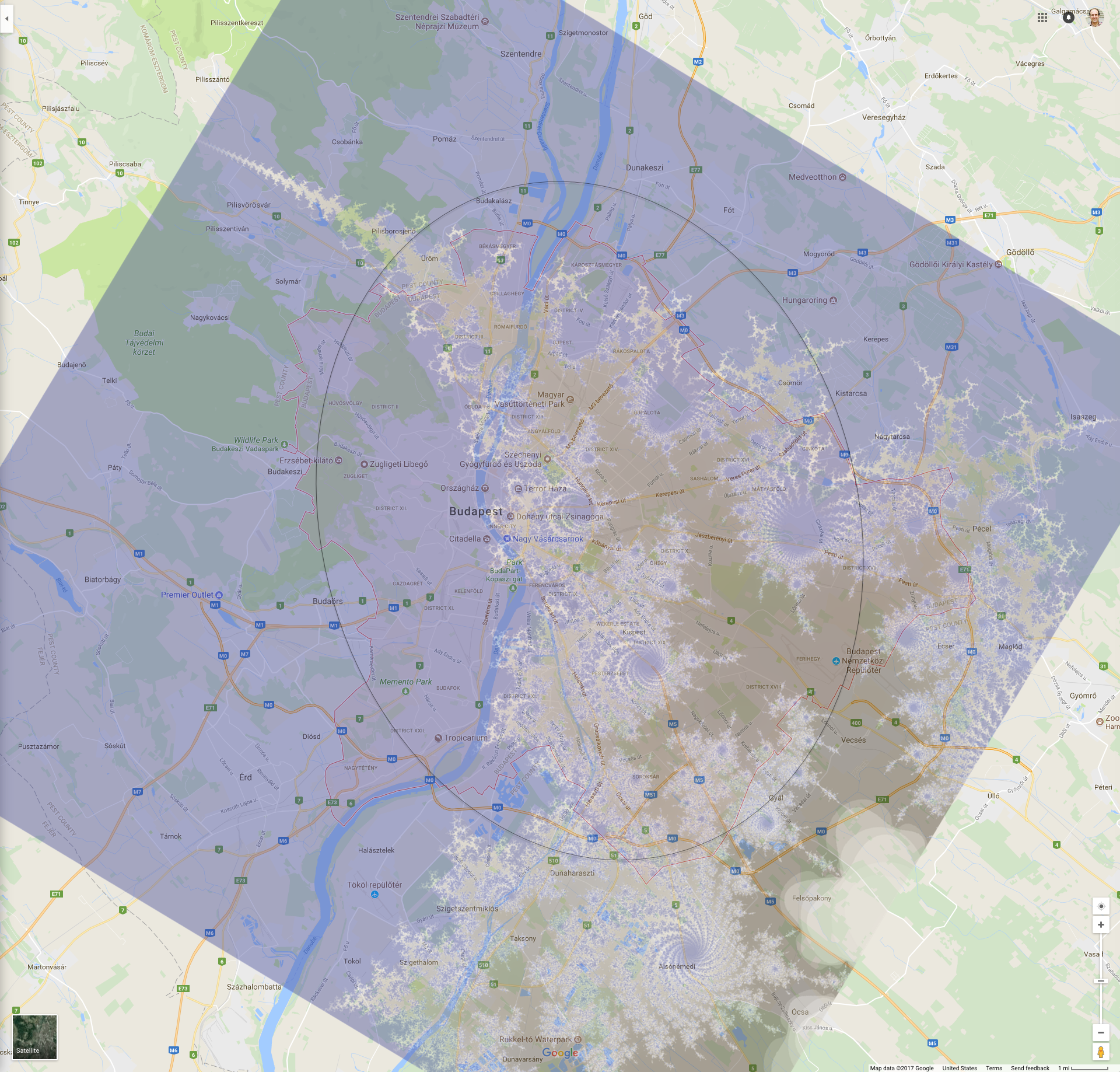

I suppose I could have done any old thing to ruin a city, but I wanted a dusting of Science! in my fiction. I thought a fractal would make a believably consistent result small enough for microscopic robots to store. I used FractalWorks, a Mac app, to generate a tiny portion of the celebrated Mandelbrot function, and overlaid this on a large screenshot of central Budapest, so its finer arcs and whorls were the length of city blocks.

Budapest map and Mandelbrot sliver

I didn’t think at the scale of blocks it could ever be so precise – if nothing else, land would collapse – so I cut out the Lake using an image editor’s predictive selection tool, to make the edges sloppy and eroded.

Both the pink and white areas are products of the fractal. The white is the Lake itself, while the pink represents Soft Lands, areas of shifting underground streams through which nanites recharge, around which smugglers tunnel.

It’s been a huge help to have the reference. Putting my characters on a literal map lets me figure out relative distances, and helps me imagine the land and the city that might grow from it.

I also thought further about my mechanical monster’s makeup. Where Lake meets land has always been seductively quiet, since earliest drafts. Instead, let the meeting of Lake and Soft Lands be a place of churn and upheaval, the turbulence of nanites going into and out of dormancy around the buzz of other nanites quantumly-uncertain just where their strange fractal stops. I have a heart murmur too.

It’s easier to name things in the context of the city’s weird sense of humor now, and I’m looking at it as more impressively built than previous drafts. Where before it was falling apart and hastily erected, now I see it as printed and reprinted, strange but regular, by the same artificially-intelligent drone “taxibots” that run the city services. This has new virtues and a very different look. And some rewriting.

If this map gets reproduced in the book, I don’t want the plain line drawing quality of most novel maps. Rather I’d commission a graphic artist to generate a cityscape, degrade that so it looked like a 12th-generation-photocopy of an old image, have all the landmarks written in sloppy marker. At top: “Welcome to Pest where you will likely die.” At bottom: “Wanna know more? Live and learn.” -

Robots vs. androids in fiction (go robots!)

Among the characters in my new novel is a collective of former package-delivery drones that, after a war, evolved themselves into a taxi service for their damaged city.

From the earliest drafts, I saw them as small flying saucers, with only a central trunk/harness to carry goods or a seated cross-legged person. It took a little time before I saw the plot and character possibilities of robots without hands or appendages. It meant that they had continued to evolve themselves to depend on people, both as customers and even as mechanics, like Thomas the Tank Engine.

I also gave them a limited vocabulary of green and red lights, suitable for bargaining over fares, but akin to the radiation-wounded Christopher Pike on old Star Trek. This made for a stranger, more labored interaction, but one familiar to anyone who has set a digital device.

It also made it easier for the taxibots credibly to be taken for granted by the people around them while they — well, you’ll read it one day. 🙂

This is a less common take on manufactured beings. (more…) -

The pre-apocalypse

My writing group noted that my new story, though a different setting, is also a post-apolcyalypse tale, or at least post-disaster. One colleague included my novel in that theme, even though in my novel things are good, but about to get worse. It’s pre-apocalyptic, she said.

Something in that. My faith is that humanity will persist, but a lot of bad things are going to happen. By the standards of the past they already have. Like my mentor Philip K Dick, I’m less pinpointing details of the great shift, just exploring scenes after upheaval, where people have adapted to far different norms of environment and behavior. I no doubt absorbed this from my family history, for my parents fled war and Soviet occupation, and my own late 20th century life, where we took on huge social changes, and where the rest of the world changed vastly more. I greatly admire writers like Jim Shepard and Harlan Ellison, who change up place and time each story yet keep consistent in their approach and style.

Perhaps I’ll be more sensitive to this strain of pre-apocalyptic. I hope it will give me a way to glide across genre. I would enjoy writing historical. (more…) -

The future of the university

My father recently put money in my son’s college fund. My son has more than a decade before he heads to college, but what a decade that might be.

Already, online educational courses, from primary- and secondary-school initiatives like Khan Academy to university-level work, are not just spreading knowledge irrespective of distance and tuition, but inverting the traditional model. Instead of students attending school lectures and doing homework, the future promises home-viewed lectures, and coaching sessions where instructors help students execute what they learn online.

That the model of university education we’ve used for the last half-millenium will be going through some amazing creative destruction in the next decades seems a sure bet. Schools will merge, downsize, specialize. Some will go out of business. But I think the university, as an institution, has more staying power than many believe.

In the early days of online shopping, new Internet grocery ventures failed while older supermarket chains developed successful delivery systems. In hindsight it’s easy to see why — (more…) -

Science fiction as time travel

I grew up on a solid diet of science fiction, and as a young man in the 1970s and 1980s I had a wide range of style to choose from — New Wave, Old Guard, the Cyberpunks. To read them all at once was like the old Evolution of Man posters, the history of the future all in view.

Like the time-traveler who uses knowledge of the future to succeed, I became a technology early-adopter by reading science-fiction. When I saw it happening for real in the 1980s, as limited and clunky as it was, I already knew what it was going to be. Twenty years ago I even lucked into a job in the field, first learning then explaining to others just what “online” was. That job is done.

I am running out of futures.

(more…) -

Tinkerers and the Tea Party

Recently on Slashdot I read a thread about how 3-D printing — the technology of making an object layer by layer, as opposed to carving it out of a block of matter or forming it in a mold — is limited by the difficulty-of-use of 3-D design software. As threads on Slashdot do, it quickly became a forum for all kinds of venting and debate. One especially nerdy (and I mean that as a compliment) rebuttal explained a system for recreating sheet-metal parts in software, as a way of showing how “easy” it is to digitize a flat object like a gasket.

I suppose if I described exactly how to build my garage shelving out of 2x4s and plywood it would be even longer, but most people will read that post and be glad they have a hardware store to run to when their garden hose is dripping.

Tinkerers persist in society despite the vast system of production and shipping that we humans have created. This is of course usually seen as a blessing — where would we find innovation if not for such people — but the people doing this seeing are often faux-wistful columnists who would not at all be happy if they had to design their gaskets, or even their paper clips, from scratch. (more…)