In this season of love, I’m posting Valentines to inspirations for my own novel, The Demon in Business Class. This is the second – see them all here.

It’s impossible to say only one literary work taught me how to create characters, how to make them as deep and maddening as real people, how set them against each other, how to set them in their time and place.

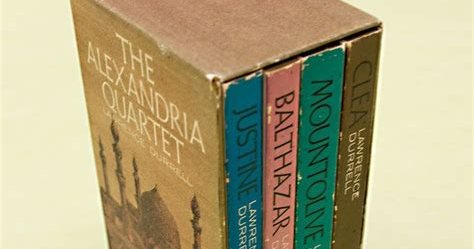

If I could only pick one, it would be Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet.

It’s not an easy work to explain in this short space: a magnificent, sprawling, story of destructive passions that hide, and enable, political intrigue. Told told over four gorgeously slumming novels (Justine, Balthazar, Mountolive and Clea), it’s set in Alexandria, Egypt in the 1930s, at the onset of both World War II and Middle-Eastern revolution.

It’s also not an easy work: elliptical, philosophical, experimental, inconclusive, and rooted in single viewpoints for such long stretches that it really takes until the third novel to see just how wrongly some characters in the first novel misunderstood their situations.

In flipping through its pages, both in my hands* and in memory, I wonder anxiously (in Harold Bloom’s sense) at its many influences on my characters — of which I was mostly unconscious during my writing, thank goodness. Zarabeth is like Justine in her sensuous character, childhood trauma, and facility with deception, but Zarabeth is an overt trouble magnet, and would bristle at being so pampered and indirect — as, in the end, does Justine herself. Gabriel has both Darley’s callowness and Mountolive’s optimism to mislead him, but happily Gabriel is more violent and less deceptive than either. Walt is wealthy like Nessim, and like him, gets in Missy a wife who, also like Justine, sets his agenda and will never stick to his bed alone.

If those were the similarities I didn’t intend for The Demon in Business Class, here’s three I did:

It’s cosmopolitan. The Quartet only has only one setting, unlike Demon‘s dozen, but empires come to Alexandria, and have for two millennia. Few books give one such a sense of meeting our whole world and its history in one place, which is likely why I so responded to it while reading it during my own wanderings across the in-flight map.

It’s personal. I led this homage by talking about characters, and the Quartet keeps the focus on them, even while so slowly revealing an actual plot that won’t leave anyone unscathed — but there’s no saving or destroying the world here. The story stays rooted in the characters’ lives.

It’s about the end of youth. I almost wrote that it was about growing up, but growing up is something we do in our teens. 1st Corinthians famously notes the putting away of childish things, but when we first close the toychest, the adult world is new to us. The Alexandria Quartet is about when we start to see just how old and big the world really is, and how little of its time we’ll actually get to take part in.

In Mountolive, the Quartet‘s third novel, the novelist Pursewarden bitterly calls Jesus an ironist for blessing the meek, given what the rest of us do to their inheritance. In that at least, Demon‘s characters differ in their imitation of Christ, learning by example not statements. As Walt says to Gabriel, “You’re what, thirty? Jesus died at thirty-three. Get cracking.”

*I have the 1961 Dutton paperback edition, pictured, though not the box. It’s a lovely set I sought across many used bookstores, and the last literary novel I read in mass-market format.